The dinosaur known by the common name “shark-toothed lizard” is obviously not a shark, nor a lizard. In fact, if the Carcharodontosaurus were to have a closest living relative it would be a member of the order Crocodylia. The inside of its skull and inner ear, as well as its brain size, are similar to some modern reptiles. Though Charles Depéret and J. Savornin were the first to unearth some of the first Carcharodontosaurus fossils during a North African dig in 1927, it was a discovery in the 1990s that gave a clearer picture of this creature. A 1996 expedition to Morocco led by paleontologist Paul C. Sereno revealed a huge skull and partial skeleton of a Carcharodontosaurus saharicus. It appeared to be larger than North America’s Tyrannosaurus rex and a close relative to South America’s Giganotosaurus. The skull alone measured 5 feet 4 inches long. Just a year after celebrating that find, Sereno and paleontologist Stephen Brusatte found a second species: Carcharodontosaurus Iiguidensis. Also a member of the Carcharodontosauridae family, C. liguidensis had many similar characteristics to the C. saharicus, but Brusatte found apparent differences in the bones in the nose and around the brain.

One thing was for sure: This “shark-toothed lizard” was a hunter. Its short arms sprouted sharp, three-fingered claws and it had serrated, 8-inch-long teeth made for eating meat. Along with its sharp claws and impressive teeth, the bipedal Carcharodontosaurus was speedy and sported a wide body, weighing around 16,000 pounds. It grew up to 45 feet in length and stood 17 feet high, making it one of the largest carnivores on the planet, according to scientists. With such an intimidating physical structure, you might think the Carcharodontosaurus would be free of rivals. Not the case. Though it is suspected they could take on some of the largest dinosaurs alive, including the sauropods, their biggest rival was the Spinosaurus, also known as the “spine lizard,” which grew up to 60 feet in length. Dr. Angela Milner, deputy keeper of paleontology at London’s Natural History Museum, has speculated that the Carcharodontosaurus might have been a victim of “allopatric speciation.” This is when “biological populations are physically isolated by a barrier, in this case a seaway, and evolve in reproductive isolation,” she said in a NHM London press release. “If the barrier breaks down later, individuals of the populations can no longer interbreed.”

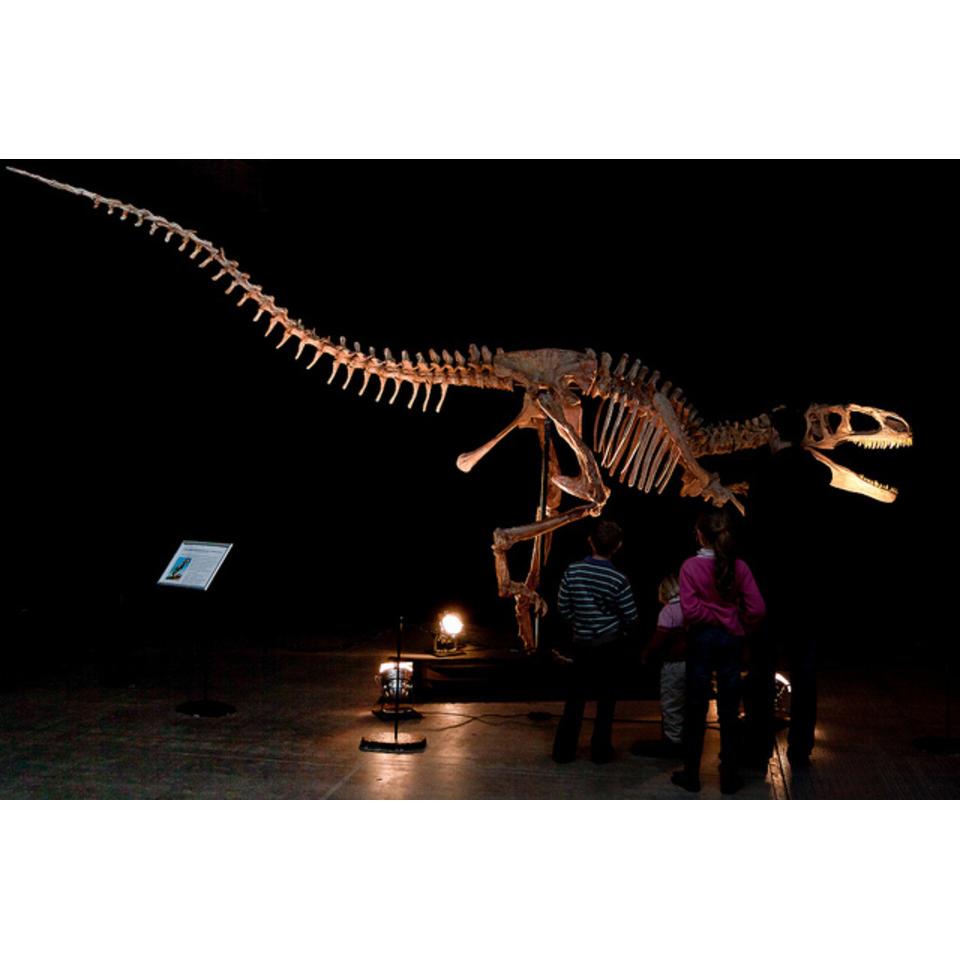

CARCHARODONTOSAURUS FOSSILS FOR SALE